|

Christoph's Tape Pages - Comparison Test Revox A77 / B77 / A700 from Audiophile 03/2003 |

|

ReView

|

|

Almost everything that runs on electricity or electronics loses its appeal within a short period of time.

That is the rule for products such as cell phones, TVs, or video recorders.

The exception to this is a range of hi-fi or high-end devices, which tend to increase in appeal and therefore in value over time.

The new AUDIOphile ReView section is now dedicated to these gems.

And comprehensively so.

Experienced authors do not limit themselves to simply photographing these products and describing how wonderful life was back then.

Or, at best, giving tips on where to get these magnificent instruments repaired—they also engage deeply with the sound.

The AUDiophile Laboratory, in turn, measures these high-fidelity milestones of yesterday using today's technology.

AUDIOphile ReView kicks off with tape machines from Revox—the legendary A 77, B 77, and A 700. They are indeed not new, and today they are still worth every euro invested in them. Anyone who owns one of these can consider themselves lucky. And because they are so important to enthusiasts and collectors, AUDIOphile ReView is kicking off with a super test from page 8 to page 27. One of the most experienced experts on these machines, Jürgen Schröder, has studied them in great detail. Not just for this article: Schröder writes the story of his life here. |

|

|

|

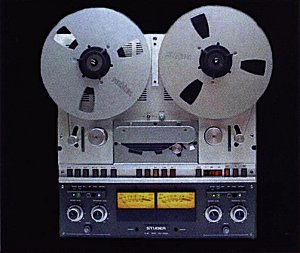

||

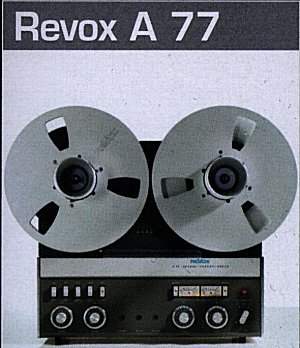

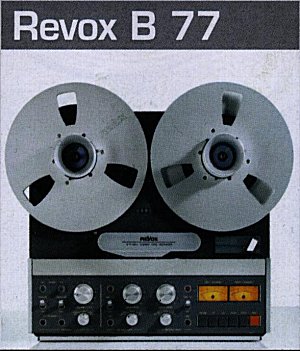

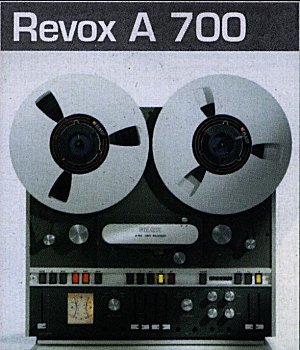

| The Revox A 77 was manufactured from 1967 to 1977. It was the first fully transistorized tape recorder with three motors and three heads for home use. The robust die-cast chassis and the smooth-running, precise capstan motor were outstanding. The picture shows a Revox A 77 Mk IV from 1976. | Introduced in 1977, the Revox B 77 improved on the proven A 77 concept with a larger chassis, which in practice provided better ergonomics. In addition, the drive control has been refined and the signal path optimized. The Revox B 77 Mk II pictured here dates from 1987. | With a quartz-controlled drive offering three tape speeds and extensive tone control, the Revox A 700, introduced in 1973, was aimed at the discerning hi-fi enthusiast. With a built-in stereo mixing console and a wide range of special effects, it was the dream of ambitious tape enthusiasts. | ||

|

At the beginning of the 1970s, the reel-to-reel tape recorder finally shook off its nerdy image.

The tape machine was born. |

||||

|

Even though owning my own tape recorder was my most cherished childhood dream, there were times when a Revox would have been out of the question for me.

The fact that I now own two magnificent pieces from this traditional Swiss brand is an exciting story.

It dates back to the year 1970:

The dawn of the hi-fi stereo era freed the tape recorder from its stuffy image as dad's Sunday toy for recording family celebrations or early childhood attempts at speech—the tape recorder became the tape machine.

This heyday of open-reel devices gave rise to many high-quality home audio machines.

The most famous among them were called Uher Royal de Luxe, Philips N 4407, Saba TG 543 Stereo, and, of course, Revox A 77.

Why can I still spontaneously recall these names? It's quite simple: Because back then, tape recorders held the same significance for all music and technology enthusiasts that computers do today. Similar to how kids today download MP3 files from the Internet, recording popular radio programs was a kind of national pastime back then. When Hans Verres presented his evening programs on Hessischer Rundfunk or Achim Sonderhoff on WDR, they were accompanied by hundreds of thousands of attentive listeners who eagerly awaited the next track with rapt attention and their fingers poised on the pause button. Every sound was meticulously recorded on tape, optimally controlled, of course, so that there was no noise or distortion—fragments of announcements, crackling, or cut-off sounds were absolutely unacceptable. Back then, at the tender age of eleven, I had neither a tape recorder nor any in-depth technical knowledge. However, what I shared with many magnetic tape fans was an aversion to Revox. Of course, we knew that the A 77 was simply “the best.” There were plenty of arguments in favor of this: In most devices, dozens of shift rods, all kinds of wheels, and contact sliders were subject to extreme wear and tear when the start button was pressed. Dozens of connecting rods, all kinds of small wheels, and contact sliders moved into the right position when the start button was pressed. In the A 77, however, only the lift magnet pressed the rubber pressure roller against the sound track with a satisfying click. |

||||

| Technology in Detail | ||||

|

|

|

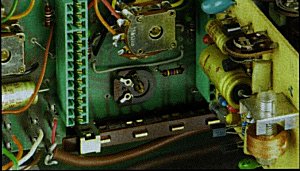

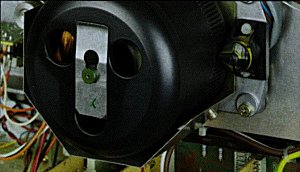

||

| The powerful external rotor winding motors of the A 77 (left) achieved high rewinding speeds even with heavy metal spools. | Thanks to its torsion-resistant die-cast chassis, the A 77 was extremely robust mechanically. It also stood out thanks to its service-friendly design. | Thanks to its modular design with plug-in modules, the Revox A 77 can be optimally adapted to the respective application. | ||

|

Conventional tape machines had a single, central motor that was responsible for both tape transport and winding and unwinding the reels.

The unwinding belt tension, which is important for reliable belt-head contact, was generated by vulnerable combinations of felt disc slip clutches in the winding plates and pressure felts in front of the clay heads.

Not so with the A 77: it had three motors—a winding motor on the left, a winding motor on the right, and the capstan motor for the tape drive.

Unwinding and winding tension was generated without wear by means of precisely measured tension values for the winding motors.

The powerful external runners were also capable of moving large spools with a diameter of up to 26.5 centimeters.

Compared to the 18-inch reels commonly used at the time, this doubled the playing time with the same tape material and speed.

What's more, the three-motor design resulted in a truly breathtaking rewinding speed.

Most tape recorders in the early 1970s were dual-head devices: In addition to the eraser head, they had a combination head that was responsible for both recording and playback. Depending on the selected operating mode, the electrical amplifier stages were also switched over. Although this was a component-saving solution, it was extremely compromised and also caused malfunctions. The A 77, on the other hand, worked with separate heads for recording and playback. Head spacing optimized for the respective operating mode (wide for recording, narrow for playback) improved the controllability and high-frequency response. In addition, the use of separate amplifier stages for the recording and playback heads made it possible to listen to the recording for immediate quality control during the recording process (tape monitoring). Three heads, three motors, a robust die-cast chassis, rear tape control, and space-saving vertical operation with large reels—its uncompromising design made the A 77 absolutely unbeatable at the time. It was the only tape machine that transferred studio technology to the home environment without any ifs or buts. Of course, at over 1800 marks, it cost significantly more than the competition. But what provoked us tape fans was not their high price, but their untouchability—our rejection of Revox was a rebellion against the establishment, solidarity with the weaker ones, the cultivation of imperfection: Anyone could take good records with the elite A 77, but with a highly unpredictable Telefunken—that was true artistry. |

||||

| Technology in Detail | ||||

|

|

|

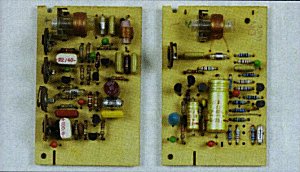

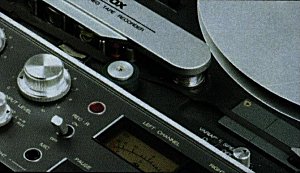

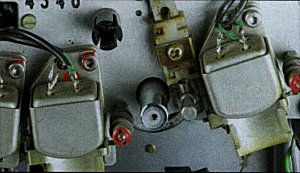

||

| The recording (left) and playback amplifiers of the A 77 can be improved with newer components. The white block capacitors should be replaced in any case. | There are two adjustment controls in the connection shaft of the B 77 for adjusting the output voltage. DIN sockets were still standard at that time. | The head support of the B 77 provided sufficient space for cutter work. The practical cutting device (right) was part of the basic Revox equipment. | ||

|

My first tape machine was a Philips N 4511 built in 1976:

It implemented the three-head, three-motor concept at less than half the price of an A 77, making it something of a Revox Populi.

Although she gave a thoroughly impressive performance, the joy she brought did not last too long:

The tapes, some of which were matted on the back for better winding properties, sanded down the tape head pressure felts row by row—cleaning instead of using was the motto.

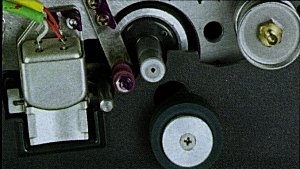

Although an A 77 did not have such problems, Revox was still taboo for me. I preferred to flirt with the Teac A-3300 or the Tandberg 10 X. The sting left by the Revox employee in the white Black Rose shirt at the Düsseldorf HiFi Fair in 1977 ran too deep. “What can I get you?” he asked smugly, well aware of the high status of his brand—and the fact that, as a poor trainee, I couldn't afford the newly launched Revox B 77 anyway. Another ten years would pass before I was exiled to Revox. In 1987, I began studying sound engineering at the School of Audio Engineering in Frankfurt. For analog editing exercises, there was a room equipped with four tape machines. Three of them were from a Japanese manufacturer, and the fourth was a Revox B 77 Mk II—the very model shown in the lead image. When booking cutting time, I was always delighted when I managed to get the B-77 slot: Unlike other machines, the Revox offered variable tape speeds, sufficient space in front of the heads for marking cut points, a reverse switch for swapping stereo channels, and an excellent headphone amplifier that not only sounded good but could also produce decent volume. In short: the B 77 was a real luxury editing suite. But it wasn't just the features and ergonomics that made working with the B 77 such a pleasure—it was also the feel of it. The controls were solid, easy to grip, and ran smoothly, the display characteristics of the large VU meters with integrated peak indicators were chosen for practicality, and the short-stroke buttons for drive control did not tire the fingers, even during long editing sessions. When switched on, the sound capstan motor briefly revved up with a fine, turbine-like whistling sound and then shone with absolute silence. If I did have to switch to another machine, it was always a culture shock—I suddenly found myself enjoying the Revox world. Some time later, I worked as a technical supervisor at SAE alongside my studies and was also responsible for maintaining the tape machines. While I had to replace a keypad for the drive control almost every week on the Japanese devices, the B 77 did not experience a single service call despite the toughest conditions. Hundreds of diligent students worked on it, shredding miles of quarter-inch tape—as the photos prove, this left virtually no trace on her. After completing my studies, I needed a reliable master machine. For a small fee, I freed the B 77 from its dreary existence as a cutting machine and converted it into a high-speed version with tape speeds of 19 and 38 centimeters per second. A weekend-long project, but entirely doable with service instructions, measuring tapes, and the necessary parts. I also took this opportunity to change the frequency response equalization from the American NAB standard to the European CCIR/DIN standard. The difference: The milder NAB equalization (lECII) offers slightly more dynamic reserves in the high frequency range and is therefore more suitable for home audio equipment with the lower tape speeds of 9.5 and 19 cm/s. CCIR equalization (IEC 1), on the other hand, produces less noise and is therefore the better choice for studio machines running at 38 cm/s, as the head dynamic range of the tape is sufficiently large at this speed. The conversion was not only exciting and educational, but also a complete success in terms of sound: At the time, several colleagues admitted without envy that my updated B 77 was taking off like a rocket. |

||||

| Technology in Detail | ||||

|

|

|

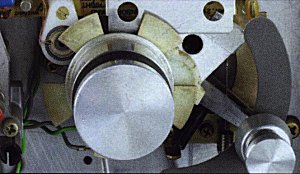

||

| For the high-speed version of the B 77, a capstan with a larger diameter (center of image) is used than in the standard version. | The B 77 adopted the high-precision, wear-free capstanmotor from the A model. On the right side of the image is the inductive speed sensor. | Instead of an impulse head for controlling slide projectors, AUDiophile laboratory manager Schüller installed a quarter-track playback head in his A 700 (right). | ||

|

But if you say “B,” you also have to say “A.”

Having acquired a taste for it, I seized the opportunity shortly afterwards to purchase a Revox A 77 at a bargain price.

Visually in good condition, as the lead photo shows, it was not in the best technical condition.

Carelessly converted to a low-speed version with tape speeds of 4.75/s and 9.5/s in a specialist workshop, the capstan motor ran at fluctuating speeds and the tape head adjustment was completely off.

Of course, I wanted to restore the A 77 to its original condition with 9.5 cm/s and 19 cm/s:

Since the recording and playback amplifiers had to be changed anyway, I equipped them with low-noise transistors and optimized the equalization for a smoother playback frequency response.

This was not unfamiliar territory, as a study of the service manual revealed a surprising number of similarities to the B 77, which I knew very well.

The result of this rejuvenation treatment was astonishing:

At 19 cm/s, the A 77 easily outperformed its younger sister.

Even today, their performance is still excellent.

Joachim Pfeiffer, who recently used this machine in his plant for a few weeks, was completely blown away by its qualities—ultimately, it was this that sparked the idea for this story.

Through targeted component replacement and careful calibration, it is possible to get a lot more signal-to-noise ratio and sound out of the Revox 77s. Older A models in particular still have plenty of scope due to their rather tame settings. My most extreme experience in this regard was a Revox PR 99 MK II equipped with wide-track (butterfly) tone heads, the professional sister of the B 77: After thorough calibration, she allowed herself to be controlled to such an extent that the recording could hardly be deleted. In any case, it is astonishing what reserves the concept of the 77 models offers. The British company Itam built a large 8-track half-inch machine based on the A-77 drive. |

||||

| Technology in Detail | ||||

|

|

|

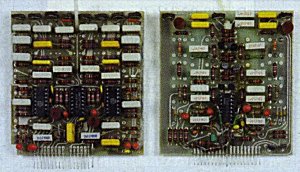

||

| The tape movement detector (center) and tape tension sensor lever (right) on the A 700 operated wear-free thanks to inductive coupling. | The recording (left) and playback amplifier modules of the A 700 used integrated circuits instead of discrete transistors. | The base board of the A 700 appears tidy thanks to the use of integrated circuits. At the bottom right is the preamplifier for the phono MM input. | ||

|

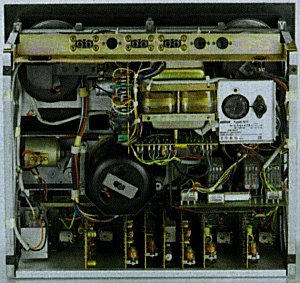

But despite all their positive features, the 77 series also had its weaknesses.

The biggest:

The winding motors operated at constant torque during recording and playback.

Therefore, the tape tension was lowest when the left spool was full.

Under unfavorable conditions, A 77 and B 77 therefore tended to be unstable in terms of level and phase at the beginning of the tape.

However, as the winding diameter decreased, the belt tension gradually increased to relatively high values.

This caused the belt speed to drop toward the end of the belt if the contact pressure of the rubber pressure roller was set a little too low.

Such weaknesses were not an issue for the third Revox in the group, the impressive A 700: It detected the current tape tension using a sensor lever and kept it at a constant level using an inductive electronic control circuit—a costly but elegant solution. Although it also featured Revox's primary virtues of a three-motor die-cast drive and three-head technology, the A 700 went its own way compared to the mechanically and electrically closely related 77 series: Designed as the central component of a hi-fi system, it incorporated a full-fledged preamplifier with switchable tone controls and a stereo mixing console section—it even had a phono input for turntables with magnetic systems. This range of functions required complex circuit technology that was virtually impossible to implement using conventional, discrete design. The A 700 also employed dozens of integrated circuits in the signal path—a state-of-the-art circuit design for its time. Even in the particularly sound-critical recording and playback amplifiers, the A 700 featured operational amplifiers—which, from today's perspective, are virtually prehistoric specimens. Audiophiles also claim that, in terms of sound quality, the A 700 is inferior to the 77s with their discrete stages. A bold thesis. It is interesting to note, however, that Revox used the discrete circuit technology of the 77 models for the significantly newer PR 99 recording/playback amplifiers. When it comes to tape handling, however, the A 700 clearly has the upper hand in the Revox trio. Their drive also formed the basis for the famous A 67/B 67 machines from Revox's professional division Studer—one of the most successful series of lightweight studio equipment ever. |

||||

| The professional offshoots | ||

|

|

|

| The PR 99 Mk II was the professional sister of the B 77. It had transformer-balanced inputs and outputs and an electronic counter. | Studer used the tape-driven mechanism from the Revox A 700 for the B 67. The B 67 was primarily used in broadcast trucks. | |

|

And now? Does this extensive technical digression culminate in a big tape machine shootout?

Certainly not—the technical requirements are too different for that.

The A 77 operates at 9.5/19 and NAB equalization, the B 77 at 19/38 and CCIR-DlN equalization, while the A 700 can handle all three speeds but equalizes according to NAB—even with the same tape material and the same speed, these are too different starting conditions.

The A 700 shown by laboratory manager Peter Schüller should also be given a fresh cell treatment.

In any case, comparing the sound of tape machines is more of a description of the situation:

A less technically sophisticated machine that has been perfectly calibrated often sounds better than a theoretically superior machine that has not been optimally adjusted.

So let's just forget about it.

To be honest, I don't really care which of the three Revox machines actually sounds best. After all, each of them has its own unique charm—I've already grown fond of the A 77 and B 77, and I'm just getting to know the A 700. So forgive me for my betrayal, you Akais, ASCs, Ferrographs, Sonys, Tandbergs, Teacs, and Uhers: Auch ich konnte mich dem Mythos Revox auf Dauer nicht entziehen. Even I couldn't escape the Revox myth in the long run. While the spare parts situation for many famous tape machines looks more than precarious, Revox pilots can look to the future with confidence. Wear parts are outrageously expensive, but they are available. And if you don't want to do it yourself, you can contact one of the many service workshops still available or Revox directly. That's basically the end of my story. However, the reason I told them has not only to do with my passion for Revox. For me, high-quality open-reel devices are still the ultimate sound recording medium. I remember well that I transferred the song “The Race” by Yellow from CD to my B 77 for editing a commercial—and what I heard from the tape blew me away: It was as if the music suddenly had the space it needed to unfold completely. This is precisely why renowned musicians today prefer analog recording in the studio. Is it pure anachronism to buy a used tape machine in the age of hard disk recorders? Certainly not. AUDIOphile recommends: Take advantage while prices are still low—only a few sellers are aware of the impending renaissance of open-reel devices. The Philips advertising slogan for the N 4520 tape recorder summed it up perfectly: From here, there is no way back. |

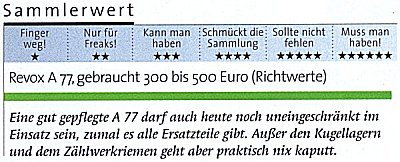

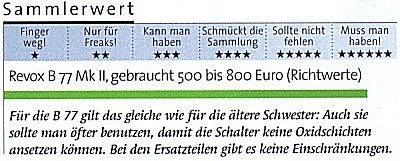

||

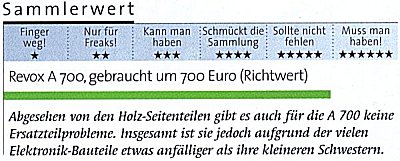

| How audiophiles rate it | ||

| COLLECTIBLE VALUE: AUDIOphile not only listens to and measures the devices—another decisive factor for classification is whether spare parts and service for the classics are available in sufficient quantities. In the case of Revox tape machines, the bars could be confidently moved far to the right: Not only do they perform their primary task excellently, but in the event of a breakdown, every machine can be competently repaired, regardless of its condition. If you want to buy a refurbished old machine with a warranty, you can do so at Revox. But then an A 77 costs 1400 euros. | ||

|

|

|

|

||

| Data and technology overview | |

| Revox A77 | |

| Dimensions WxHxD (cm): | 42 x 37 x 21 |

| Weight: | 14 kg |

| Housing designs: | The A 77 was delivered in countless versions. The best known was the suitcase version shown here in a wooden case; others included the loudspeaker case and the 19-inch built-in basket. |

| Connection options: | Inputs: dynamic microphone (L + R) 2 x 6.3 mm jack (front) and 2 x RCA (rear) 1 x high level (RCA) 1 x 5-pin DIN Outputs: 1 x line out (RCA, adjustable) 1 x 5-pin DIN 1 x headphones (6.3 mm jack) |

| Technology: | Die-cast chassis with two external rotor winding motors and electronically controlled tone arm motor. Lifting magnets for brake unit and pressure arm. Full metal recording and playback head in half or quarter track technology. Fully transistorized (silicon) amplifier, NAB or DIN equalized. |

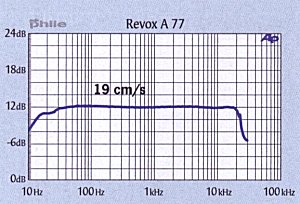

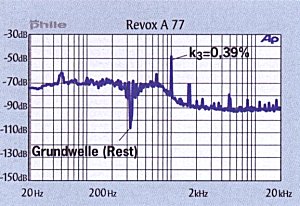

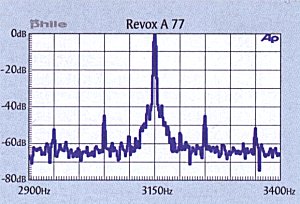

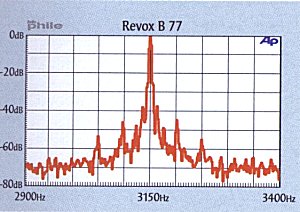

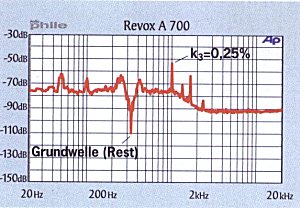

| Measured values: | When optimally calibrated, the Revox A 77 delivers an absolutely smooth frequency response, except for the low bass. Distortion is pleasingly low, and the signal-to-noise ratio is a good 66 dB. The head dynamic range is slightly lower than usual at 19 cm/s. As can be seen in Fig. 3, the strength of the A 77 is its tracking. Turntables look old in comparison. |

|

|

|

||

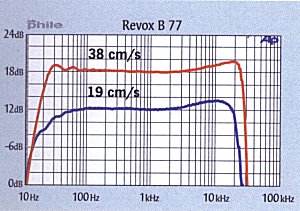

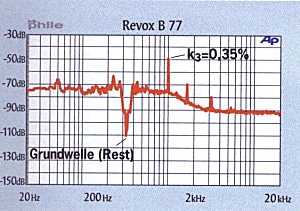

| Frequency response behind band | Distortion spectrum 0 dB, 19 cm/s | Synchronous tone spectrum 19 cm/s | ||

| Revox B77 | |

| Dimensions WxHxD (cm): | 45 x 42 x 21 |

| Weight: | 17 kg |

| Housing designs: | Like its predecessor, the B 77 was available in numerous variants. The best-selling model was the suitcase version shown here in a gray Nextel case. The 19-inch built-in basket is rather rare for the B 77. |

| Connection options: |

Inputs: dynamic microphone (L + R) 2 x 6.3 mm jack (front) 1 x high level (RCA) 1 x 5-pin DIN Outputs: 1 x line out (RCA, adjustable) 1 x 5-pin DIN 1 x headphones (6.3 mm jack) |

| Technology: | Die-cast chassis with two external rotor winding motors and electronically controlled tone arm motor. Variable tape speeds. Lifting magnets for brake unit and pressure arm. Full metal recording and playback head in half or quarter track technology. Fully transistorized amplifiers, NAB or DIN equalized. |

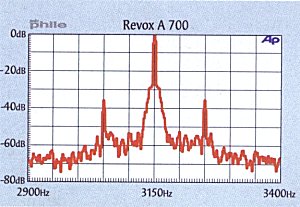

| Measured values: | The slight emphasis on high frequencies with Emtec's modern LPR 35 tape could be compensated for by higher pre-magnetization. However, this would compromise the good dynamics and low distortion, which increases again at high speeds compared to 19 cm/s (68.5/71 dB bass/treble dynamics). The speed variation even reaches values of around +/-0.03%. |

|

|

|

||

| Frequency response behind band | Distortion spectrum 0 dB, 38 cm/s | Synchronous tone spectrum 38 cm/s | ||

| Revox A700 | |

| Dimensions WxHxD (cm): | 48 x 46 x 21 |

| Weight: | 24 kg |

| Housing designs: | The standard version of the A 700 was anthracite-colored. The cladding panels were bolted directly to the chassis. |

| Connection options: |

Inputs: Microphone (L + R) 2 x 6.3 mm jack, transformer-balanced 2 x high level (RCA) 1 x phono magnet (RCA) 1 x DIN 5-pin Outputs: 2 x line out (RCA, fixed and adjustable) 1 x power amplifier (5-pin DIN) 2 x headphones (6.3 mm) |

| Technology: | Die-cast chassis with two tape-pull-controlled external rotor winding motors and electronically controlled tone arm motor. Three tape speeds. Varispeed device. Solenoid for brake unit and pressure arm. All-metal recording and playback head. Amplifier equipped with integrated circuits, NAB or DIN equalized. |

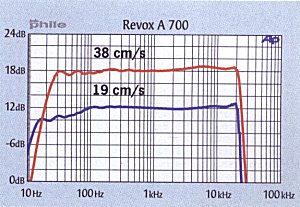

| Measured values: | Head mirror resonances cause a steep drop below 30 Hz at 38 kHz. Otherwise, balanced frequency responses can be achieved with each band. In terms of dynamics, the A 700 achieves peak values: signal-to-noise ratio 69/69.5 dB and head dynamic range 66/72 dB (at 19/38 cm/s). With +/- 0.074% at 19 cm/s, the tracking is also impressive. |

|

|

|

||

| Frequency response behind band | Distortion spectrum 0 dB, 38 cm/s | Synchronous tone spectrum 38 cm/s | ||

|

This test report was taken from Audiophile magazine 03/2003 magazine with the kind permission of Vereinigte Motor-Verlage GmbH & Co. KG.

Author: Jürgen Schröder Photos: ? |

||||

| ↑ back to top ↑ | ||

|